Userkaf's pyramid is part of a larger mortuary complex comprising a mortuary temple, an offering chapel and a cult pyramid as well as separate pyramid and mortuary temple for Userkaf's wife, queen Neferhetepes. Userkaf's mortuary temple and cult pyramid are today completely ruined and difficult to recognize. The pyramid of the queen is no more than a mound of rubble, with its funerary chamber exposed by stone robbers]

Discovery and excavations

The entrance of the pyramid was discovered in 1831 by the Italian Egyptologist Orazio Marucchi. but was not entered until 8 years later in 1839 by John Shae Perring, who took advantage of an existing tunnel dug into the pyramid by tomb robbers. Perring did not know for sure who the owner of the pyramid was and attributed it to Djedkare Isesi (reign 2414–2375 BC), a late 5th dynasty pharaoh. After his investigations Perring buried the robbers tunnel which remains inaccessible to this day. The pyramid of Userkaf entered the official records a few years later in 1842 when Karl Richard Lepsius catalogued it in his list of pyramids under number XXXI. Since Perring had already buried the robbers tunnel by that time, K. R. Lepsius did not investigate the pyramid any further

The pyramid was then neglected until October 1927, when Cecil Mallaby Firth and the architect Jean-Philippe Lauer started excavating there. During the first season of excavation, Firth and Lauer cleared the south side of the pyramid area, discovering Userkaf's mortuary temple and tombs of the much later Saite period. The following year, Firth and Lauer uncovered a limestone relief slab and a colossal red granite head of Userkaf, thus determining that he was the pyramid owner After Firth's death in 1931 no excavations took place on site until they were resumed by Lauer in 1948. Lauer worked there until 1955, re-clearing and re-planning the mortuary temple and investigating the eastern side of the pyramid. Research on the north and west sides of the mortuary complex was conducted starting in 1976 by Ahmed el-Khouli who excavated and restored the pyramid entrance. The entrance was, however, buried under rubble in an earthquake in 1991. More recent work on the pyramid was undertaken by Audran Labrousse in 2000

Morturary complex

Layout

Userkaf's mortuary complex: 1) Main pyramid, 2) offering hall, 3) cult pyramid; the mortuary temple comprises: 4) courtyard, 5) chapel, 6) entrance corridors and 7) causeway.

The mortuary complex of Userkaf comprises the same structures as those of Userkaf's 4th dynasty predecessors: a high wall surrounded the complex with its pyramid and high temple and there was certainly a valley temple located closer to the Nile, yet to be uncovered. The valley temple was connected to the pyramid by a causeway whose exact trajectory is unknown, even though its first few meters are still visible today

The layout of the complex, however, differs significantly from that of earlier complexes. Indeed, it is organized on a north–south axis rather than an east–west one: the high temple is located south of the main pyramid and its structures are turned away from it. Furthermore, a small offering chapel is adjoining the eastern base of the pyramid, a configuration otherwise unattested since offering chapels usually occupy the inner sanctum of the mortuary temple. Finally, immediately to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure is a second smaller pyramid complex attributed to his wife, queen Neferhetepes.

The reason for these changes is unclear, and several hypotheses have been proposed to explain them:

- The first hypothesis is that this is due to a change of ideology. The advent of the 5th dynasty marks the growing importance of the cult of the sun as hinted by the Westcar Papyrus. This is also directly evidenced by the large sun temples built at Abusir throughout the dynasty, a tradition initiated by Userkaf. Finally, the Abusir Papyri demonstrate the strong connection between the cult of the sun and the mortuary cult of the pharaohs of this dynasty: offerings for a deceased ruler were first consecrated in a sun temple before being dispatched to his mortuary temple. Thus, Userkaf located his mortuary temple to the south of the main pyramid so that the sun would shine directly into it all year round.

- The second hypothesis holds that Userkaf chose to return to 3rd Dynasty (c. 2670–2610 BC) traditions: not only did he choose to construct his mortuary complex on the north-east corner of Djoser's complex but its layout is similar to that of Djoser. Indeed, both are organized on a north–south axis and both have their entrances located at the south-end of the eastern side.

- The third hypothesis proposes that Userkaf's choice is due to practical considerations. Nabil Swelim discovered a large moat completely surrounding Djoser's enclosure, some places as deep as 25 metres (82 ft). This moat might be a stone quarry for material used during the construction of Djoser's step pyramid. If for some reason it was important for Userkaf to locate his mortuary complex on the north-east corner of Djoser's, i.e. between the enclosure and the moat, then there was not enough space available for the mortuary temple to be located on the east side. Thus the local topography would explain the peculiar layout of Userkaf's complex.

Mortuary temple

Fragment of a relief representing Userkaf from his funerary temple.

Userkaf's mortuary temple layout and architecture is difficult to establish with certainty. Not only was it extensively quarried for stone throughout the millennia, but a large Saite period shaft tomb was also dug in its midst, damaging it.

Modern reconstructions of the temple nonetheless show that it shared the same elements as all mortuary temples since the time of Khafre (reigned c. 2570 BC). However, just as with the complex, the layout of the temple seem to differ significantly from those of Userkaf's predecessors. The causeway entered the pyramid enclosure at the southern end of the east wall. There the entrance corridor branched south to five magazine rooms as well as a stairway to a roof terrace. To the north a doorway led to a vestibule and then to an entrance hall That in turn led to an open black-basalt floored courtyard bordered on all sides but the south one by monolithic red granite pillars bearing the titles of the king. A colossal head of Userkaf was found there, the second oldest monumental statue of an Egyptian ruler after the Great Sphinx, now in the Egyptian Museum. The head, which must have belonged to a 5-metre-high (16 ft) statue, represents Userkaf wearing the Nemes and Uraeus. The walls of the courtyard were adorned with fine reliefs of high workmanship depicting scenes of life in a papyrus thicket, a boat with its crew and names of Upper and Lower Egyptian estates connected to the cult of the king.

Two doors at the south-east and south-west corners of the courtyard led to a small hypostyle hall with four pairs of red granite pillars. Beyond were storage chambers and the inner sanctum with three (Ricke) or five (Lauer) statue niches where statues of the king would have been placed, facing the pyramid to the north. Contrary to other mortuary temples, the inner sanctum was thus separated from the pyramid by the courtyard. The only remains of the mortuary temple that are visible today are its basalt paving and the large granite blocks framing the outer door.

Offering chapel

A small offering chapel is adjoining the eastern side of the main pyramid and is barely visible today. It consisted of a central two pillared room with a large quartzite false door and two narrow chambers on the sides. Like the mortuary temple, the chapel was floored with black basalt. Its walls however were made of Tura limestone and granite and were adorned with fine reliefs of offering scenes

Userkaf's temple with the ruins of the pyramid of Neferhetepes in the background.

Cult pyramid

In the south-west corner of Userkaf's mortuary complex is a small cult pyramid. This pyramid was destined to receive the Ka of the deceased pharaoh and thus might have housed a statue of Userkaf's Ka. It stood 15 metres (49 ft) high with a base 21 metres (69 ft) long and its slope is identical to that of the main pyramid at 53°. The position of the cult pyramid within the complex is unusual, the cult pyramid being normally located in the south-eastern corner. This difference is certainly linked with the peculiar overall north–south layout of Userkaf's complex with the south-eastern corner hosting the entrance to the mortuary temple.

The core of the pyramid is made of roughly hewn limestone blocks similar to those of the main pyramid. These were disposed in two layers and finally clad with fine Tura limestone which fell victim to stone robbers. Consequently, the poor quality pyramid core was exposed and degradated rapidly with only the two lowest layers of the pyramid still visible today

The pyramid has a T-shaped substructure with a descending corridor leading to a chamber with a gabled roof. Similarly to the main pyramid, the substructure was constructed in a shallow open pit dug into the ground before the pyramid construction started and is therefore located just below ground-level

Main pyramid

Construction

1858 photography of the north side. In the background, the

Pyramid of Djoser.

Userkaf's pyramid is located on the northeast corner of Djoser's step pyramid complex. The pyramid was originally around 49 metres (161 ft) high and 73 metres (240 ft) large with an inclination of 53° identical to that of Khufu's great pyramid for a total volume of 87,906 m3 (114,977 cu yd). The core of the pyramid is built of small, roughly-hewn blocks of local limestone disposed in horizontal layers. This meant a considerable saving of labor as compared to the large and more accurately-hewn stone cores of 4th Dynasty pyramids. However, as the outer casing of Userkaf's pyramid fell victim to stone robbers throughout the millennia, the loosely assembled core material was progressively exposed and fared much worse over time than that of the older pyramids. This explains the current ruined state of the pyramid.

The pyramid core was constructed in a step-like structure, a construction technique similar to that of the 4th dynasty although the building material was of a significantly lower quality. The outer casing of the pyramid was made of fine Tura limestone which certainly ensured Userkaf's construction an appearance similar to that of the glorious 4th Dynasty pyramids. There was however no red granite paneling over the lower part of the pyramid as in the case of the Pyramid of Menkaure

Substructures

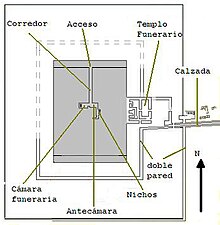

Substructure

[1] of the pyramid Userkaf A = descending passage, B = granite

portcullis, C = magazine chamber, D = antechamber, E = Userkaf's burial chamber, F = gabled ceiling.

The pyramid does not have internal chambers, the chambers being located underground. These were constructed in a deep open ditch dug before the pyramid construction started and only later covered by the pyramid. The entrance to the underground chambers is located north of the pyramid from a pavement in the court in front of the pyramid face. This is different from the 4th dynasty pyramids for which the entrance to the internal chambers is located on the pyramid side itself. The entrance was hewn into the bedrock and floored and roofed with large slabs of white limestone, most of which have been removed in modern times.

From the entrance a 18.5 metres (61 ft) long, southward descending passage leads to a horizontal tunnel some 8 metres (26 ft) below the pyramid base.The first few meters of this tunnel were roofed and floored with red granite. The tunnel was blocked by two large portcullis of red granite, the first one still having traces of the gypsum plaster used to seal the portcullis

Behind the granite barrier the corridor branches eastward to a T-shaped magazine chamber which probably contained Userkaf's funerary equipment. The presence of such a magazine chamber, located under the base of a pyramid, is unique of all the 5th and 6th dynasty pyramids

At the south end of corridor lies an antechamber, which is located directly under the tip of the pyramid. The antechamber is oriented on the east–west axis and leads west to the king's burial chamber. The burial chamber has the same height and width as the antechamber, but is longer. At the western end of the burial chamber Perring discovered some fragments of an empty and undecorated black basalt sarcophagus which had been originally placed in a slight depression as well as a canopic chest. The chambers are protected from the pyramid weight by a gabled ceiling made of two large Tura limestone blocks, an architecture common to all pyramids of the 5th and 6th dynasties. The chambers are lined with the same material, while the floor pavement was lost to stone robbers

Pyramid complex of Queen Neferhetepes

It was common for Old Kingdom pharaohs to prepare the burials of their family close to theirs, and Userkaf followed this tradition. Thus 10 metres (33 ft) to the south of his funerary enclosure, Userkaf had a small separate pyramid complex built for his queen on an east–west axis. The pyramid is completely ruined and only a small mound of rubble can be seen today.

Discovery

The pyramid of the queen was first recognized in 1928 by C. M. Firth following his first excavations to the south of Userkaf's main pyramid. One year later in 1929, he proposed that the pyramid be assigned to Queen Neferhetepes, Userkaf's wife and the mother of Sahure. It was not before 1943 that Bernard Grdseloff discovered the tomb of Persen, a priest at the court of Userkaf and Neferhetepes. His tomb is located in the immediate vicinity of Userkaf's complex and yielded an inscribed stone giving the name and rank of the queen. This stone is now on display at the Egyptian Museum of BerlinFurther evidence confirming the assignment of the pyramid to Neferhetepes was discovered by Audran Labrousse in 1979 when he excavated the ruins of the temple Consequently, the small pyramid complex has been attributed to her.

The funerary chamber of the queen's pyramid exposed by stone robbers.

Pyramid

The queen's pyramid originally stood 16.8 metres (55 ft) high with a slope of 52°, similar to that of Userkaf's, with a base 26.25 metres (86.1 ft) long. The core of the pyramid was built with the same technique as the main pyramid and the cult pyramid, consisting of three horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar. The core was undoubtedly covered with a fine Tura limestone outer casing, now removed. In fact, the pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry in later times that it is now barely distinguishable from the surroundings and its internal chambers are exposed.

The entrance to the substructure is located on the pyramid's northern side and consists of a descending passage leading to a T-shaped chamber. This chamber was located under the tip of the pyramid and is oriented on an east–west axis like the rest of the queen's pyramid complex. It has a pented roof made of large limestone blocks, a construction technique common to all pyramid chambers of the 5th dynasty. The substructure is thus a scaled-down version of Userkaf's without the magazines

Mortuary temple

The queen's pyramid complex had its own separate mortuary temple, which was located on the east of the pyramid in contrast to Userkaf's complex. This difference may be explained by the small dimensions of the temple which allowed it to be oriented to the east in the usual fashion. Access to the temple was located in the south-east corner of the enclosure wall. The entrance led to an open courtyard that stretched from east to west. The ritual cleaning and preparation of the offerings took place here. Because of the extensive degradation suffered by the temple, reconstruction attempts are somewhat speculative. From the ruins, archaeologists propose that the temple comprised an open colonnade, possibly made of granite,] a sacrificial chapel adjoining the pyramid side, three statue niches and a few magazine chambers. No traces of a cult pyramid were found onsite. In the halls of the temple were depictions of animal processions and offerings carriers moving towards the Shrine of the Queen.

Later alterations

The pyramid of Userkaf was apparently the object of restoration work in antiquity under the impulse of Khaemweset (1280–1225 BC), fourth son of Ramses II. This is attested by inscriptions on stone cladding showing Khaemweset with offering bearers

During the 26th Dynasty (c. 685-525 BC) Userkaf's temple had become a burial ground: a large shaft tomb was dug in its midst thus rendering modern reconstruction of its layout difficult. This indicates that by the time of the Saite period, Userkaf's temple was already in ruins