Yet despite its later date, it exactly reflects traditional pharaonic architecture and so provides an excellent idea of how all the temples once looked. Edfu is also very large: the second largest in Egypt after Karnak Temple.

The provincial town of Edfu is located about halfway between Luxor (115km away) and Aswan (105km) and 65km north of Kom Ombo. A very popular destination, Edfu is included in virtually all Egyptian tour itineraries and can be reached by taxi or by cruise on the Nile followed by a caleche ride (Horse carriage).

History

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt. After his death in 323, his successors ruled Egypt under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. This was the last dynasty of independent Egypt. The Ptolemies were Greeks but presented themselves to the Egyptians as native pharaohs and closely imitated the traditions and architecture of pharaonic Egypt.The Temple of Horus at Edfu was built during the Ptolemiac era on top of an earlier temple to Horus, which was oriented east-west instead of the current north-south configuration.

The oldest part of the temple is the section from the Festival Hall to the Sanctuary; this was begun by Ptolemy III in 237 BC and completed by his son, Ptolemy IV Philopator. The Hypostyle Hall was added by Ptolemy VII (145-116 BC) and the pylon was erected by Ptolemy IX (88-81 BC). The final touches to the temple were added under Ptolemy XII in 57 BC.

The falcon-headed Horus was originally the sky god, whose eyes were the sun and moon. He was later assimilated into the popular myth of Isis and Osiris as the divine couple's child. Raised by Isis and Hathor after Osiris' murder by his brother Seth, Horus avenged his father's death in a great battle at Edfu. Seth was exiled and Horus took the throne, Osiris reigning through him from the underworld. Thus all pharoahs claimed to be the incarnation of Horus, the "living king."

The Temple of Edfu was abandoned after the Roman Empire became Christian and paganism was outlawed in 391 AD. It lay buried up to its lintels in sand, with homes built over the top, until it was excavated by Auguste Mariette in the 1860s. The sand protected the monument over the years, leaving it very well preserved today.

In 2005, a visitor center and paved parking lot were added to the south side of the temple, and in late 2006 a sophisticated lighting system was added to allow night visits.

What to See

When facing the Pylon from the south, don't miss the Birth House is on the left. This colonnaded structure was the site of the annual Festival of Coronation, which reenacted the divine birth of Horus and the reigning pharaoh. Around the back of the building are reliefs of Horus being suckled by Isis. A Birth House is a Greco-Roman feature that would not have been part of older pharaonic temples.Erected by Ptolemy IX (88-81 BC), the Pylon was one of the last features to be added. Standing 37m high, it is among the largest in Egypt. Its reliefs show a later Ptolemaic ruler, Neos Dionysos (Ptolemy VIII), smiting his enemies before Horus the Elder.

Beyond the Pylon is the spacious Court of Offerings, where people could enter to make offerings to the image of Horus. The court is surrounded by columns on three sides and is decorated with festival reliefs. Beginning on the inner walls of the Pylon and continuing around the court along the bottom of the wall, the reliefs depict the Festival of the Beautiful Meeting, during which Hathor's image sailed from Dendera to spend some intimate time with Horus in the sanctuary of the Temple of Edfu before sailing back.

Beneath the western colonnade are reliefs of Ptolemy IX (88-81 BC) making offerings to Horus, Hathor and Ihy; his successor is shown with the same deities across the way.

At the back of the Court of Offerings, outside the Hypostyle Hall, are a pair of black granite Horus statues. One stands taller than a man and is a favorite photographic subject of tourists; the other lies legless on the ground.

The rectangular Hypostyle Hall was built under Ptolemy VII (145-116 BC) and has two rows of six pillars supporting an intact roof. The ceiling has astronomical paintings symbolizing the sky.

If you have a flashlight, you can examine two interesting rooms on the entrance wall: the Chamber of Consecrations to the left, where the king or priest dressed for rituals; and the Library on the right, where sacred texts were kept and reliefs depict Sheshat, the goddess of writing. On the far (north) wall, reliefs of Horus have been destroyed by Christian iconoclasts.

Next is the Festival Hall, which marks the beginning of the oldest part of the temple, built 237-212 BC under Ptolemy III and IV. During festivals, this hall was decorated with faience, flowers and herbs and scented with incense and myrrh. Offerings of libations, fruit and sacrificial animals were brought in through the passageway on the right and nonperishable offerings were stored in a room to the left. The room in the back left (northwest) corner is the Laboratory, where recipes for incense and unguents are inscribed on the walls.

A small doorway, decorated with splendid reliefs of the sacred barques of Horus and Hathor, leads from the Festival Hall into the Hall of Offerings. During the New Year Festival, the image of Horus was carried up the ascending stairway on the left to be revitalized by the sun, then carried back down the descending stairway. Reliefs on the walls of both stairways depict the event, but a flashlight is necessary and locked gates may make access difficult.

This hall leads into the Sanctuary of Horus, the holiest part of the temple. The sanctuary centers on a black-granite shrine that was dedicated by Nectanebo II, making it the oldest relic in the temple. This once contained the gilded wooden cult image of Horus. Next to the shrine is an offering table and the ceremonial barque (barge) on which Horus was carried during festivals. Reliefs on the right (east) wall of the sanctuary show Philopator (Ptolemy IV) worshipping Horus, Hathor and his deified parents in the sanctuary.

The corridor surrounding the sanctuary contains several interesting rooms worth exploring. On the left (west) is the Linen Room, flanked by chapels to Min and the Throne of the Gods. In the back, a set of rooms nominally dedicated to Osiris has colorful reliefs of Horus receiving offerings (left room), a life-sized depiction of Horus' barque (middle room) and reliefs of his avatars (rear room in the right/east wall). Continuing south in the right corridor is the New Year Chapel, with an impressive blue-hued relief of the sky goddess Nut stretched across the ceiling.

Returning to the Festival Hall, head through the passage in the east wall for access to the external corridor where the priests tallied tithes based on the nearby Nilometer.

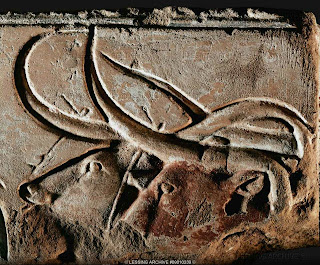

The passage in the west wall leads to a corridor with reliefs of the triumph of Horus over Seth. Specifically, they depict a Mystery Play that was performed as part of a festival ritual, in which Seth appears as a hippopotamus lurking beneath his brother's boat. At the end of the play, the priests cut up and ate a hippo-shaped cake.

Quick Facts

| Site Information | |

| Names: | Edfu Temple; Temple of Horus at Edfu; Temple of Edfu; Apollopolis Magna |

| Location: | Edfu, Upper Egypt, Egypt |

| Faith: | Ancient Egyptian |

| Dedication: | Horus, Apollo |

| Category: | Egyptian temples |

| Architecture: | Egyptian |

| Date: | 257-37 BC |

| Size: | Pylon: 37m high |

| Status: | ruins |

| Photo gallery: | Edfu Temple Photo Gallery |

| Visitor Information | |

| Coordinates: | 24.978108° N, 32.873315° E (view on Google Maps) |

| Lodging: | View hotels near this location |

Note: This information was accurate when published and we do our best to keep it updated, but details such as opening hours can change without notice. To avoid disappointment, please check with the site directly before making a special trip.